If there is no disagreement with the title, then discussion is pointless. When I first heard the idea that “there are many truths,” I was startled. Today, I have come to conclude that, indeed, reality can be multiple.

At the age of six, I saw a ghost. At that time, the ghost I saw was a truth for me. It was a singular truth because I witnessed it with my own eyes. The ghost was dressed in white, as tall as a traditional wooden oil-press, and was playing a flute.

That ghost, once accepted as truth, has since been invalidated by the arguments of philosophers and the discoveries of science. It was not my eyes but my mind that saw the ghost. Thus, the ghost became two truths: one from my childhood and another in the present. This perhaps explains why, in court, the truth given by a witness is examined through cross-examination. The opposing lawyer questions the witness to test their version of the truth. If I had been summoned as a witness, I would have sworn that I had truly seen a ghost. But if asked today, I would admit it was a hallucination — and that would be the truth now.

The spiritual philosopher Aurobindo Ghosh acknowledges both the Creator and the universe (Brahman) as reality. He argues that creation arises from consciousness, which he considers the ultimate truth — formless consciousness. He advocates a singular truth, considering the Creator and the universe as two expressions of one truth.

In contrast, Adi Shankaracharya regards the world as illusion (Mithya) and Brahman alone as truth. He attempts to explain the concept of truth by comparing dream experiences to waking reality. I saw the ghost not in a dream but in waking life, and yet, it was not real.

Sigmund Freud suggests that preconscious thoughts, reasoning, and analysis manifest in dreams. His psychological interpretation closely aligns with Shankaracharya's conception of the illusory nature of the world (Maya).

When mothers gathered to press mustard seeds at the traditional oil-press (kol), I found the place eerily quiet, contrary to my expectations. It was there that I saw the ghost. Later, I learned that the women had gone to another press believed to yield more oil. The ghost appeared only at the deserted oil-press near the communal water source natural spring (Padhera). But I alone saw it; no one else witnessed it.

The wooden oil-press, a traditional mechanical device used for pressing oil for millennia, disappeared with the rise of water mills and modern engines. Though no longer in use, remnants of these wooden presses can still be found in some villages.

The ghost vanished the moment I ran home in fear, but the image of that scene remains etched in my memory. The fear lingered well into adolescence. Even when everyone was downstairs, I would feel frightened going to the upper floor in the dark. I hid my fear from others, then quickly turned on the light to reassure myself that no ghost was present.

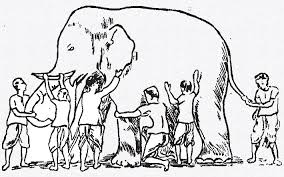

Now that I no longer believe in ghosts, I realize that truth is not singular. Even a factual experience may not qualify as an ultimate truth. When forming an opinion on a new subject, we are guided by our pre-existing beliefs. German philosopher Immanuel Kant made this point, and neurophysicist Richard Gregory concurred, adding that our perception depends on prior knowledge. Twentieth-century thinkers Thomas Kuhn and George Berkeley also argue that perception is shaped by prior experience.

When I saw the ghost, it was the first time. But my sister’s earlier stories of ghosts were already in my mind. I encountered unexpected silence where I expected festivity. Into that silence, my mind projected the ghost it had imagined. I now understand that my physical eyes did not actually see what I thought I saw. I saw the ghost my sister had described.

At the core of these arguments lies the question of consciousness — its origin and nature remain subjects of scientific inquiry. From this focal point arises the debate: is truth singular or manifold?

Since Aurobindo’s and Shankaracharya’s truths differ, there must be more than one truth. Only if one of them is proven absolutely wrong can we assert that truth is singular. Suppressing inquiry in the name of spiritual dogma may achieve this, but for those committed to academic curiosity, the only path forward is to reconcile diverse views and continue the search. For scholars, truth must be plural.

Dayananda Saraswati also argued that individuals form opinions in proportion to their knowledge. A lack of knowledge results in erroneous beliefs. For example, it was my sister’s story — my only source of "knowledge" — that caused me to "see" a ghost. Dayananda developed his philosophy during India’s anti-colonial struggle, using religious sentiment to unite Indians. That is why proponents of the Sanatan tradition emphasized the Bhagavad Gita's teaching — "Perform your duty without attachment to the results" — as a religious tenet.

Before British colonialism, traditional Indian debates (Shastrartha) centered on attaining liberation (Moksha). The Rigveda discusses duties for building a happy and prosperous society, assigning roles based on social levels and stages of life. The ideal characters of Ramayana and Mahabharata reflect this family-oriented structure — Kauravas, Pandavas, Ram, and Sita all belong to family units. Bhishma’s tragic solitude, burdened by duty, reveals the deeper emotional message of these epics.

In contrast, Buddha renounced his family and comforts in pursuit of wisdom to eliminate suffering — making renunciation the path to truth for him. Most religious teachers, however, consider the pursuit of familial and moral ideals as the truth.

Marx and Lenin regarded the idea of a socialist society as the truth. Mao Zedong considered the New Democratic Revolution as the truth. Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre, despite believing life to be absurd, saw rebellion and the pursuit of freedom as moral truths. B. P. Koirala regarded democratic socialism as truth.

Western mainstream ideologies view the reform of capitalist economics and critique of communism as truth. For Bin Laden and his followers, building an Islamic world through acts like the 9/11 attacks was their version of truth.

Thus, whatever a person believes in becomes truth for them. There are many truths in the world. As long as others' truths do not interfere with one's own, they should be accepted. A society where diverse truths coexist peacefully becomes a more harmonious place.

Therefore, respecting others’ truths must be a core value of the academic world.